Laurentius chapel

Laurentius is the patron of the church. The metal grid – his standard attribute – refers to his death as a martyr. Laurentius didn’t want to give the church silver and holy books to emperor Valerianus, so he provoked Valerianus by giving it all to the poor. As retribution, Laurentius was tortured on a metal grid above a fire.

Laurentius as a patron

Laurentius is a patron now, but that hasn’t always been the case. He lived in Rome, in the third century, and took care of the poor on behalf of the church. He was also responsible for the holy books and the church silver. Emperor Valerianus made it illegal for Christians to profess their beliefs. The pope didn’t abide by this law and was sentenced to death. The same fate awaited Laurentius.

But first, Laurentius had to hand over all valuables to Valerianus. A great opportunity for one final good deed! Laurentius thus divided the money between the poor and organized a procession towards the emperor. “Behold, the treasures of the church”, he said, while pointing to the poor.

This act of bravery had its costs: Laurentius was tortured on a metal grid above a fire. After his death he was canonized. Laurentius carries the grid on which he was mistreated with him, as befits a true saint.

Lost masterpieces

Caesar van Everdingen, Jacob van Oostsanen, Romeyn de Hooghe: all famous artists who created masterpieces for the church. Nevertheless, we’re still missing two other great names: Maarten van Heemskerck and the “Master of Alkmaar”. There was a time when their works also adorned the interior of the church. However, both these works of art were sold – and with that two great masterpieces were lost. A life-sized print of Maarten van Heemskerck’s triptych was placed in the church in the nineteen-nineties. When its quality deteriorated, artist Pauline Bakker created a new triptych.

Maarten van Heemskerck

Eight meters long and five meters in height: the immense triptych of master painter Maarten van Heemskerck used to be on display at the high altar. It was made in 1538, depicting the crucifixion of Christ and Laurentius’ life as its main themes. The showpiece survived the Iconoclastic Fury, but didn’t fit the religious convictions of the protestants, who gained ownership of the church. It was sold to Sweden in 1581, where it’s still on display in the Linköping Cathedral. The loss wasn’t made up for until four hundred years later, in the nineteen-nineties. Then, a life-sized print was placed in the original spot at the high altar. When the print’s quality deteriorated, artist Pauline Bakker was allocated the task to create a new triptych.

Master of Alkmaar

Feeding the poor, visiting prisoners or taking care of the ill: these are three of the “Seven Works of Mercy”, moral deeds for good Christians to help their fellow humans. The “Master of Alkmaar” painted these seven panels in 1504. It’s his most famous work and an exceptional example of early Dutch painting. The message is clear: those who do good, will be rewarded forever. For the same reason, there was a little box hanging near the painting, where churchgoers could donate some money. At the moment, it’s on display at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which bought the work in 1918. With the revenue, the church – in financial distress at the time – was renovated.

The Great Saint Laurence Church

The church: 500 years in Alkmaar

This church has been the focal point in the daily lives of many inhabitants of Alkmaar for more than a thousand years. The church has been a place to celebrate, to mourn, to play, to say one’s prayers, and to come together and meet each other. This is a pivotal place. The tombstones, the pulpit, the carvings made by pilgrims in one of the pillars: there are traces of history throughout the church. Marks of people who have visited, as well as signs of tempestuous events can be found anywhere. Superior examples of religious artworks, such as the magnificent organ and the ceiling painting, are reminiscent of prosperous times. Not everything has stood the test of time, but the stories remain alive and relevant. Discover more than ten centuries of history and unearth the church’s hidden treasures and fascinating chronicles.

Worship and devotion

Until 1573, this was a Catholic church. In that time, there was no separation of church and state yet, which meant the city council was responsible for the church. The bigger and higher the church, the higher the regard for the city. The worship of God and His saints required a lavishly decorated church, with altar pieces, statues of saints, murals, and colourful windows. In the Catholic era, the high altar was the most important location in the church: the place where the high mass was officiated. The high altar is at the east side of the church, where the sun rises: a symbol for the light of Christ.

At the service of the word

After the Reformation, Protestantism was the state religion. In 1573, the church turned protestant. The Bible is central to Protestantism and all manifestations of worship were unwanted, so the church became less and less decorated.

In some cities, the Iconoclastic Fury took place – however, Alkmaar remained relatively peaceful. Gradually, statues of saints and altars were removed. During this period, the city council remained responsible for the upkeep of the church. The church was the focal point of Alkmaar’s protestant elite.

After 1795, freedom of religion as well as the separation of church and state were introduced. The municipal government stopped contributing to the maintenance of the church, which quickly led to a shortage of funds. Out of sheer necessity, some valuable artworks were sold.

Culture and connection

The church lost its religious function in 1996: its ownership and maintenance are now in the hands of two foundations. Restorations and maintenance are paid for through subsidies and donations.

The church used to be a shelter where citizens of Alkmaar could practice their religion and come together, and where children could play safely. To this day, you can still enjoy this magnificent monument, come visit concerts or expositions, get married or celebrate other festivities. Uniting people continues to be fundamental to the Great Saint Laurence Church.

The boardroom

For years, this room was a sort of prison. People who had been “unruly” were given a choice: either spend the night here, or pay a fine of three guilders. Later, the space was renovated and decorated; it became a presentable meeting room for the church elders.

The oldest playable organ

This organ has been played on for five centuries. It’s the oldest still playable organ in The Netherlands, built by Jan van Covelens in 1511. It’s a miracle it still exists, because the pipes were supposed to be used for the construction of the main organ in 1638. Fortunately, there were enough means to pay for new organ pipes, so that this small organ could be preserved. It functioned as a backup instrument when the grand organ wasn’t available. Except for a few minor adjustments, much of the organ is still in its original state.

Floris V

This is where the famous Floris V was buried. Or at least, that is what the name of this casket suggests: “The tomb of Floris V”. The reality is different: when Floris was killed in 1296, his body was laid out here in Alkmaar. He was buried in Rijnsburg, but the citizens of Alkmaar kept his intestines. This was not unusual in the Middle Ages, when it came to monarchs: their body, heart and intestines were often kept in different places.

In the fifteenth century, a tombstone was placed saying Floris’ intestines were buried here. This wooden casket was made a century later. As a result of the painting, the casket seems to be made out of marble and natural stone; suitable for a sovereign.

Floris V was an important count. He left his mark on Dutch history by getting political matters in order. He defeated uprisings, built citadels and reorganized the government. As a peacemaker, he acquired the nickname “the common man’s God”.

Photo credit: Regionaal Archief Alkmaar

Ship by Michiel de Ruyter

Hanging a ship in a church, also called a votive ship or church ship, is a very old custom. This custom dates back to the Middle Ages and was traditionally a Catholic custom. These boats were usually donated by skippers who promised their patron saint such a boat after a rescue.

This one refers to the blow that Michiel de Ruyter inflicted on England by sailing through the chain in the Thames and causing a lot of damage to the English defense. The poem on the sail praises his achievements. We now think about this in a more nuanced way: his past is not without controversy because of his share in the slave trade. Before the outbreak of the English naval wars, De Ruyter visited slave colonies in the Caribbean. In 1665 he helped liberate Fort Elmina from the English, which was used by the West India Company for slave trade. Because of this, the trade continued.

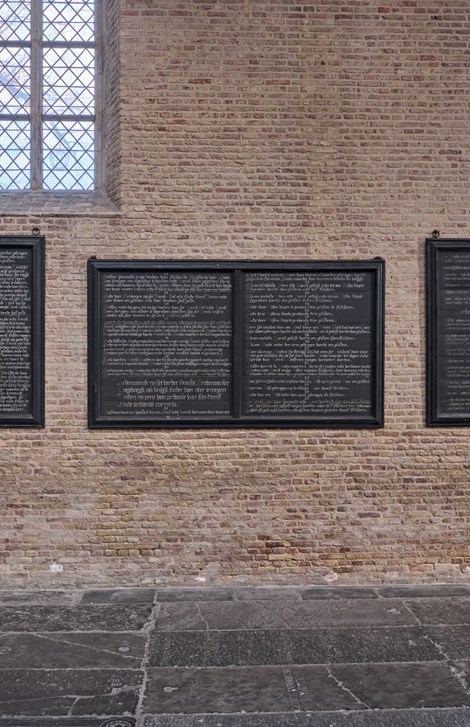

Funeral regulations

These three solemn black plates, with faint gilding still visible on a number of letters, represent the articles of the former funeral regulations of the Grote Kerk. Each item has a number and with the slightly smaller board in the middle, they are in the right order. We don't know why that board is smaller. It may have previously hung above a door with the larger signs on either side. With some effort, the articles are still readable, especially if you know that the letter s looked like an f at that time.

The Last Judgement

Vault paintings

Jacob Cornelisz (War) van Oostsanen is the earliest Amsterdam artist known by name.

He was born around 1470 in Oostzaan and moved to Amsterdam around 1500, where he settled as a painter and print artist. He bought a house annex studio in Amsterdam, Kalverstraat 62, a property which now houses a clothing store. In 1520 he also bought the adjacent property.

These vault paintings were visible to all churchgoers, as opposed to many altar pieces in chapels or choirs, which were not accessible to everyone. Even though the depiction could be complicated for some, the story and message of The Last Judgement was generally known. One is constantly reminded of what is to be expected at the end of time: make sure you behave well, for if you don’t...

Dating

The painting shows the date 1518. This was probably put there by a carpenter who had renewed some parts. A plank he replaced may have had a signature with this date. The painting was completed in 1519. Therefore the painting can be dated to 1516-1519.

A reputable grave

Having your own crypt with a tombstone and a mourning plaque was a sign you were an esteemed citizen of Alkmaar. Carel de Dieu (1700-1789) was mayor of Alkmaar for years. He often underscored the fact that he was a descendant of a wealthy family. He bought the best situated crypt of the church. On top of that, his own descendants had a mourning plaque made with a coat of arms: in exchange for a large sum of money, it was hung in the chancel. The tradition to hang mourning plaques in the church, ended abruptly in 1795, when the French ruler prohibited this practice. It didn’t fit the guiding principles of “equality, liberty, and fraternity”.

Photo credit: Regionaal Archief Alkmaar.

The Last Judgement

Vault paintings

Jacob Cornelisz (War) van Oostsanen is the earliest Amsterdam artist known by name.

He was born around 1470 in Oostzaan and moved to Amsterdam around 1500, where he settled as a painter and print artist. He bought a house annex studio in Amsterdam, Kalverstraat 62, a property which now houses a clothing store. In 1520 he also bought the adjacent property.

These vault paintings were visible to all churchgoers, as opposed to many altar pieces in chapels or choirs, which were not accessible to everyone. Even though the depiction could be complicated for some, the story and message of The Last Judgement was generally known. One is constantly reminded of what is to be expected at the end of time: make sure you behave well, for if you don’t...

Dating

The painting shows the date 1518. This was probably put there by a carpenter who had renewed some parts. A plank he replaced may have had a signature with this date. The painting was completed in 1519. Therefore the painting can be dated to 1516-1519.

Library

In the late Middle Ages, many churches had a library, called a Librije. They were often owned by the city and church with hundreds of books on chains that could be viewed. They can still be seen in Zutphen and Enkhuizen. The one in Alkmaar was closed at the beginning of the nineteenth century and the books eventually ended up at the Regional Archives, where they are now carefully stored. The room itself has been renovated: a large Gothic window is no longer visible and a ceiling was installed around 1940. In the near future, the atmosphere of the Librije will be made visible again. Some old books are downstairs in a display case in the ambulatory.

Model painting

The oldest work of art in the Grote Kerk is the fifteenth century scale model painting. This way, people who wanted to donate for the construction of the church could see what it would become. The tower was added to the painting at a later stage. That idea never progressed beyond the foundations that still lie beneath the paving outside the west portal and are marked with unusual stones. The painting has recently been meticulously restored by Martin Bijl. He then expressed the suspicion that the Master of Alkmaar could be the painter.

The second choir organ

The second choir organ was located on the spot where a sign describing the instrument now hangs. We don't know what it looked like, but we do know that it was smaller than the Van Covelens organ on the other side. It was later demolished to use the organ pipes for the main organ. The organist accessed this instrument via the stairs from the main portal. This access is not visible anymore. However, there should still be a considerable space between the closed wall of the church and the spiral staircase. But this will require a lot of detective work to find.

Decorative choir screen

This oakwood screen is one of the church’s gems. The refined gothic carving was made five centuries ago. In the Catholic era, its function was to divide the churchgoers from the choir. In the protestant era the two doors were crafted, to make sure the choir was more easily accessible for big groups during Communion and funeral services. The statues of saints were removed during the same period. The choir screen was renovated in 2012.

Photo credit: Regionaal Archief Alkmaar

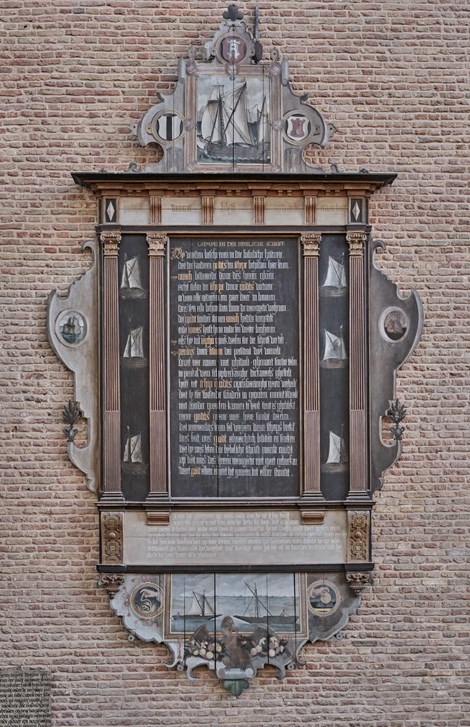

Skipper's board

The Schippers sign from the Protestant period is reminiscent of the disappeared Schippers altar from the Catholic period. The Boaters' Guild probably hung this sign on the spot where their altar stood and was demolished. The sign has enough details to tell a long story, but when passing by the visitor immediately sees that it has a 'good' and a 'bad' side. On the right side it is light and the sails have a full tailwind. On the bad side it is dark and the sails are slack. It is without a doubt the most special sign in the Grote Kerk.

The Great Window

The Great Window, which was unveiled in 2023 becauseof 450 years of 'Alkmaar Ontzet'. An 'Ontzet' window was also designed for the same location in the seventeenth century, but it was removed and thrown away just a century later. This was probably due to a lack of money for maintenance and damage repairs after a storm. There is no image of that window, but a description has been preserved. It must have resembled the Leidse Ontzet window in the Sint Janskerk in Gouda. The sign hanging under the new window also served the old window.

Brass gravestone

This heavy tombstone with copper plates is a rare example of its type in the Netherlands. It has been placed upright to prevent wear of the brass plate by the shoes of visitors. It commemorates Pieter Palinck and his wife Josina van Foreest and dates to around 1550. This can also be seen in the depiction, which shows Renaissance characteristics. The palm branches at the top indicate that the couple had made the Jerusalem pilgrimage, that is, a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

To evangelize and baptize

The robust pulpit is a bit elevated so that everyone could see the pastor. In the protestant era (after 1573), this was the central place in the church. From this pulpit, the pastor proclaimed God’s Word every Sunday: always very thorough and thus often quite long. During these services, a lot of children and some adults were baptized here. That is why this place in the church is called the “baptismal area”. The pastor sprinkled the person’s head with water from a baptismal font, while reciting the baptismal texts. From that moment on, he or she was part of the church community. The pulpit was made in the seventeenth century, just like the pews across from it. Those were reserved for Alkmaar’s elite and the church wardens.

Mayor's bench

The original mayor's bench opposite the pulpit was demolished during the French period, because it was no longer appropriate for a mayor to sit in such a prominent position. When the French had left, King William I partly restored class society, so that a mayor could distinguish himself again. That is why a new bench was installed, the quality of which did not match that of the old 'Herenbanken' around the pillars of the ship.

Family chapel

During the first centuries of the existence of the church, all side chapels were intended for guilds and prominent families. The guilds were dissolved during the French period and families had no heirs or money to pay the annual fees. Ultimately, one chapel remained; that of the Jacot family of Axele. This has been moved from the north to the south side, probably to hide the technical facilities in this chapel from view. The fencing contains elements from the Italian Renaissance and was manufactured in 1630.

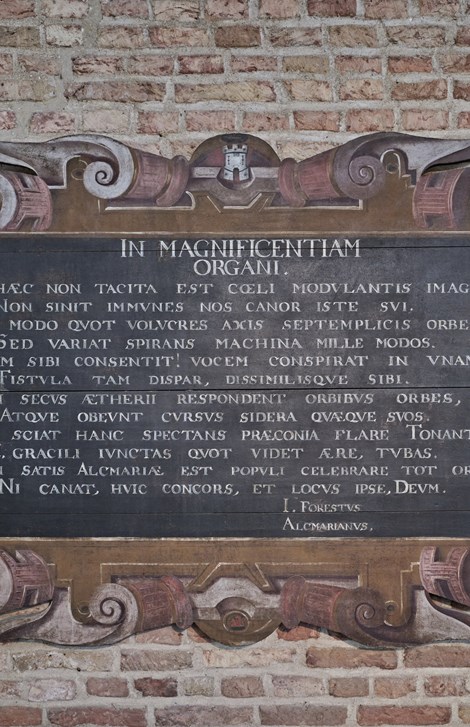

The organ & a personal chapel

The organ: a masterpiece of sound and craftsmanship

This organ is a world famous masterpiece. Many esteemed artists and craftsmen have contributed to its creation. The Hagerbeer family started building the organ in 1638; renowned architect Jacob van Campen designed the front. Caesar van Everdingen, the city’s most famous artist, painted the biblical story of King Saul after the victory over David and Goliath on the shutters. And that’s not all: there’s even a painting above the organ. Romeyn de Hooghe depicted the conflict between good and evil. Frans Caspar Schnitger modernised the organ in 1722.

Would you like to hear the stunning sounds of this instrument? There are often concerts in the church.

A personal chapel

Statues, banners, altars and colourfully painted walls: it might be hard to imagine now, but during the Catholic era there were twelve lavishly decorated chapels on the side walls of the building. They were private: with a personal chapel, often including a private crypt, prominent inhabitants of Alkmaar could demonstrate their power and prestige.

Following the Reformation (after 1573), a church had to project solemnity and simplicity. Many decorations were removed, but the family chapels remained in the church for a long time. In the French era after 1795, all coats of arms had to go; all social classes had to become equal, so every sign of differentiation was prohibited.

Basket and lifting gear

This basket with the hoisting gear was used to hoist painters and cleaners to the high wall parts of the ship. They are rare, only a few of these tools have been preserved in the Netherlands.

Baptism

Here, the sound of crying babies could often be heard. During the Catholic era (until 1573) countless children have been baptized in this spot. Baptism was an important ritual: if you’re baptized, you’re part of a community.

The old baptistery isn’t visible anymore. Hidden behind the partition is a decorative screen with the inscription “Dat rijck Gods is nu come, beke(e)rt u en gelooft de evangelio” (“The Kingdom of God has now come, convert and give credence to the evangel”). There is also a cabinet, used for baptism attributes, and in a niche in the wall there’s a small water basin.

It’s no coincidence that the baptistery is located on the west side of the church. During the Catholic era, the entrance of the church was here, under the main organ. That is why it fits to have the “commencement ritual” here.

Burying in the church

In this church, we walk on a floor made of gravestones. Thousands of deceased were buried here. To make sure there was space for all of these graves, some have been placed on top of each other, sometimes up to eight. It was expensive to be buried in the church: only wealthy citizens could afford it. Their names and coats of arms are on the covers, as well as other symbols that refer to their occupation or religion. The oldest grave is from the Middle Ages; the most recent one is from 1830. After that, burying in the church became prohibited.

From sacristy to consistory

This room was built in the sixteenth century as a sacristy. This is where priests could change clothes and where they could prepare for the mass. There was a different chasuble for every occasion, which was why a lot of closet space was needed. The valuable liturgical vessels were kept here as well.

In the protestant era, the sacristy became the consistory. It was a place where the church council came together, where the silverware was kept and where the archive got a place as well. The coat of arms of Karel V – with the two-headed eagle and the shield of Holland – is painted in the barrel vault. The city emblem of Alkmaar, as well as those of Delft and Oudewater, can be seen there too.

The scallop

The scallop on the outer side of the church is the only remaining pilgrimage symbol in this church. The church was a stopover for pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostella. The scallop was the symbol for this pilgrimage. With the scallop on their hats or coats, travelers were protected from highwaymen, and were often offered a bed or a meal.

Saenredam

A world of difference

White walls and lots of space; a real 'Saenredam interior'. Pieter Janszoon Saenredam became famous for paintings of these types of modest church furnishings. The grave markers are characteristic of this time; this church was also covered in them.

It is almost impossible to imagine what the interior was like in the Catholic period, before 1573. Color was the magic word, and it was teeming with altars, paintings, candles and banners. The walls and vaults were painted, and stained glass windows told Biblical stories. Now some works of art are still reminders of that time, such as the large organ, the vault paintings and the choir screen.

Pieter Janszoon Saenredam

Pieter Janszoon Saenredam was the first painter to take existing church interiors as his subject and to develop them in precise linear perspective. When Saenredam visited this church, he made two drawings: one of the interior, the other of the organ with open shutters, probably studies for the painting. When he died, the work was not yet finished, which could explain the absence of his signature. The people and the dog were also added later.